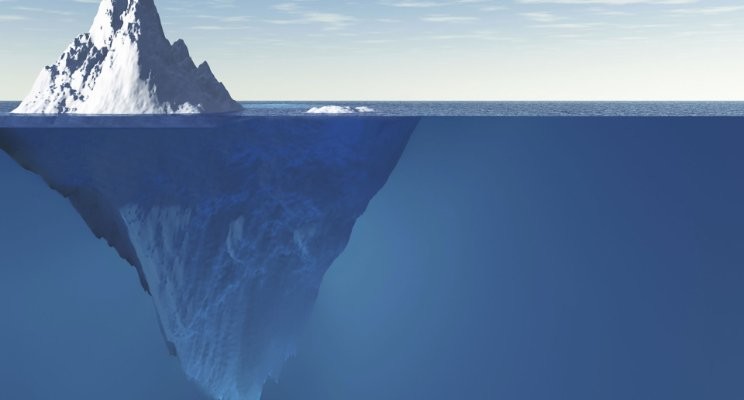

The Discovery Iceberg

It is impossible to provide an accurate budget for a discovery exercise, and any estimates will almost always change. Why? A reprint of a popular article.

Variations of this article appeared in Litigation Funding Magazine (August 2015) and Barrister Magazine (January 2016). In England & Wales the relevant term is "disclosure" but I have used the more internationally accepted term of "discovery" throughout.

The Tip of the Iceberg

Those involved in any aspect of litigation will be very familiar with providing cost estimates. These are necessary for any number of reasons, including:

- As required by the courts, with an eye on the overriding objective of proportionality.

- As part of a "beauty parade" in order to win a specific body of work.

- To manage a client's expectations and, therefore, purse.

- To secure third party funding.

- To assess whether a dispute is worth pursuing or defending, and to identify the total financial investment acceptable to the bill payer.

In my experience all of the above have some part to play, and often there will be other reasons peculiar to each individual participant's circumstances. Unfortunately, the courts of England & Wales believe "estimates" are actually "budgets". According to my Penguin English Dictionary a budget is "the amount of money available for or required for a particular purpose". Conversely, an estimate is "a statement of the expected cost of a job". So, by the courts referring to these things as "budgets" they do not expect them to change. In my discovery world, however, we estimate the likely cost of doing something based on assumptions, which always change.

In England & Wales, parties share budgets across the following distinct categories, as dictated by the seductively named spreadsheet, Precedent H (and see screenshot below):

- Pre-action costs

- Issue/statements of case

- CMC

- Discovery

- Witness statements

- Expert reports

- PTR

- Trial preparation

- Trial

- ADR/settlement discussions

Precedent H

Under "Discovery" in the April 2016 guidance notes supporting the Precedent the parties are reminded to include costs likely to be incurred by:-

- "Obtaining documents from client and advising on discovery obligations.

- Reviewing documents for discovery, preparing discovery report or questionnaire response and list.

- Inspection.

- Reviewing opponent’s list and documents, undertaking any appropriate investigations.

- Correspondence between parties about the scope of discovery and queries arising.

- Consulting counsel, so far as appropriate, in relation to discovery."

These suggested areas of cost, however, only reflect the tip of the discovery iceberg in many cases. The sort of civil matters on which I have worked over the last three decades have mainly involved very large organisations in acrimonious disputes over huge amounts of money after the failure of long-running contracts. Standard discovery is the norm, the concept of proportionality is more honoured in the breach and there is likely to be a great deal of discovery. Matters on this scale may be the minority in terms of numbers of disputes going through our courts, but they support a massive global service industry and are not decreasing in number. One just has to look at the global consolidation of service providers over the past 12 months to establish the trend.

For these major disputes the bulk of the cost of discovery occurs before actual discovery – that is, the underlying mechanics of getting to the point where a party's discovery can be effected. The majority of the iceberg is therefore hidden below the first two incredibly shallow bullet points above (obtaining and reviewing documents). Yes, Precedent H allows for contingency sums and there is a Precedent R for "budget discussions" but clearly neither of these is intended to support the frequent and inevitable re-estimates alluded to in this article.

What Lurks Beneath

Receiving an itemised bill with 50% of the legal costs neatly set out in nine clear categories as required by Precedent H, and the other 50% under the general category of "Discovery" is akin to seeing the tip of an iceberg without any suggestion of the extra danger beneath. Yet that is all that Precedent H requires parties to do. Litigation funders may be forgiven if they feel rather like the captain of the Titanic at this point. The cost of the lawyers, experts and court is usually based on the passage of time, with the only variable being the length of that passage. In the mechanics of discovery there are many, many unknowns, any one of which can wreak significant damage when (not if) one sails into it. By their very nature, these variables only reveal themselves as you hit them.

When dealing with things that change a logical solution is to factor in a contingency sum and, at the appropriate point, revise one’s estimate appropriately as the way ahead becomes clearer. However, this article will make it clear that it is extremely difficult to estimate a realistic contingency sum because of the many variables in play. Furthermore, in the adversarial litigation context it would appear that parties generally are reluctant to make applications to court to amend their so-called "budgets", perhaps fearing the wrath of a judge unfamiliar with modern discovery and the temporary nature of estimates based on shifting assumptions, or the judicial expectation that "budgets" should never change unless a tectonic shift has occurred, or all of the above. Parties are obviously even more reluctant to amend their "budgets" a second, third or fourth time yet there are many ways in which an honest estimate can change over time as a natural result of new information coming to light over that time.

Yes, there are provisions in the Civil Procedure Rules for budgets to be amended "upwards or downwards" (PD 3E7.6) but only if "significant developments in the litigation warrant such revisions". Are the variables I talk about here significant enough to warrant the submission of a revised budget for agreement or approval? How frequently can such revisions be made before doubt is cast over the accuracy of the entire budget?

It is worth noting that budgets are required by the court prior to the first Case Management Conference in order for them to decide how much of what is proposed (and for which a budget has been provided) could and should proportionately be done. One wonders about the validity of decisions made at this point if the costs cannot yet be adequately estimated.

Charted and Uncharted Waters: an Overview of Discovery

Before setting sail on a discussion of the variables that can sink the budget, the following is a broad overview of the discovery process and mechanics, written for a lay audience. I apologise if I have sacrificed detail or complete accuracy on the altar of understanding.

As soon as a party anticipates that a dispute may occur, that party is under an ongoing obligation to preserve any potentially relevant documents. To do otherwise could lead the court to draw an "adverse inference" as to the intention behind the lack of preservation. "Relevant documents" are those that may support or harm each party’s case. As trial approaches, each party provides the other with all their relevant documents, whether harmful or supportive, after having removed any documents for which they claim solicitor/client confidentiality or that are truly irrelevant. The way in which this is done is governed by formal rules and procedures. The parties thereby share a level playing field from which to prepare their respective cases for trial.

The Discovery Journey

Nowadays documents can be in paper or electronic form, or a mixture. And by "document" the courts do not mean what you think. They mean "anything in which information of any description is recorded" (Civil Procedure Rules Part 31.4). So, in its electronic form "document" does not just mean a printed or electronic Word document. "Document" includes video and audio recordings, mobile phone triangulation data, instant messaging, Bloomberg chat, Morse code, Flash animation: anything in which information is recorded.

For the purposes of this article, we shall follow a mixture of paper and electronic documents on its journey through the modern discovery process, followed by some common examples of the variables that will affect how much it is ultimately going to cost.

Preservation

A party's first step is to alert as many staff as appropriate, in both front and back office functions, that there is the possibility of a dispute and instruct them immediately to cease destroying/deleting any documents (this includes breaking the recycling of back-up media). Usually this is deliberately a very broad instruction as there is unlikely to be much focus at this stage because the Statement of Claim has probably not yet been served. As the issues in dispute become clearer, parts of the business can be freed from what rapidly can become an onerous task, especially in relation to email (email stores can grow exponentially if not managed).

Identification

In order to comply with discovery obligations the party must first find out where potentially relevant documents are stored or filed. This involves sharing the likely thrust of the dispute with the key people who may hold, or be responsible for, these potentially relevant documents to allow them to think about where one might find that which is sought. This will usually include a series of interviews with those key people and the IT staff to draw up a "map" of where to find everything. All too frequently where the front-end of the business thinks it stores things is entirely different from where the back-end IT team actually stores them. (It also quickly becomes clear that not all company policies in relation to documents are religiously followed.)

Particularly nowadays, when job security is perhaps not what it used to be, clear communication from the business to its employees about this process is crucial. Without this communication some needlessly fear for their future in the face of what is a very comprehensive audit whilst others fear for their privacy. Either way, they will act accordingly: being open can allay many fears and reduce overall cost.

Collection

Once the information and its locations are identified, someone has to go and get it. This is where paper and electronic data diverges in this example (they will come back together again later).

(A) Paper

Where possible, and following consultation with the legal team, staff will have first weeded out obviously irrelevant cabinets/boxes/files/bags/piles so as to avoid needlessly incurring cost. This will usually be based on their intimate knowledge of the matters in dispute. The remainder of the documents are securely sent to a scanning and coding company that specialises in this activity within a legal environment (the documents are now legal evidence). "Scanning" is the process of first separating the paper document (it could be a lab notebook, a document with enclosures, a bound report, etc.) into its individual parts and then taking an electronic "picture" of each part (or page) of each paper document. Following this process the original paper document can be replicated electronically. As the paper is now a series of pictures it cannot be sorted or managed in any useful way so each document is coded. "Coding" is the manual recording of basic bibliographic information (date, author, title, etc.) about the document on an associated database record that can be used for limited searching and sorting of the associated image(s). It is possible to attempt to add a layer of searchable text onto the pictures by having the computer attempt to read any typed characters and convert them into electronic words (Optical Character Recognition or OCR), although the success rate of OCR drops dramatically with the age of the document.

(B) Electronic

The collection of electronic documents is obviously very different. In this example we are going to visit the business and borrow key people’s (the "custodians") computers and take a forensically sound and exact copy of their hard drives. In addition, local IT staff will provide any back-up media spanning the broadest relevant period as well as physical and technical access to all relevant mail and file servers. We shall take forensically sound copies of the mail servers in their entirety. We are doing this because we are still unfocussed on the actual matters in dispute and therefore who all the key people will be: it is foolhardy to restrict collection at this point because that would result in further disruption to the business if we need to return and could add further cost (the price difference between a complete and a partial copy can actually be minimal). For file servers we would endeavour to target just the potentially relevant areas.

Process

All of this electronic data now needs to be unpacked and the chaff removed so that all that is left is potentially relevant material of use to a human being. This is largely an automatic process and is the first time that anyone can start to make any useful sense of the numbers of documents and the volume of space they take up (these are a couple of the variables that were completely unknown up until now). It is also the point from which humans can start to access the information to begin to understand the supportive or harmful nature of what has been collected.

Cull

Prior to beginning review it is common to cull the document population to a set more likely to be relevant, once more is known about the legal focus. Some culling techniques include applying appropriate date ranges to the documents or reducing the final population to only those documents found by searching for certain key terms or phrases. The removal of exact duplicates is also a common way to reduce numbers, as well as going straight to the latest complete email in a chain of emails rather than having to include each incremental message on the way to that final inclusive one.

Review

Review is the stage when costs really start to bite. Prior to actual discovery someone usually has to read everything that is likely to be disclosed. So the scanned and coded paper and processed electronic documents are now combined and loaded into a "review platform" (of which there are many varieties). This is a system that securely allows authorised users to search and sort all of the documents and share thoughts about them. For the purpose of discovery this is needed for three main reasons:-

1. To test for relevance.

2. To test for privilege.

3. To be aware of what supportive (to them) and harmful (to you) evidence is being provided to your opponent.

After discovery the legal team will need go on to take witness statements, prepare the case for trial and pull together the documents upon which they will want to rely at trial.

There are a myriad of electronic and manual options available to assist review (computer-aided review, predictive coding, linear review, lawyer review, managed review, etc.) but these are beyond the scope of this article.

Disclose

Once the process has reduced all of this to a relevant, unprivileged discovery set it is exchanged with the other side, usually as data and images on one or more hard drives.

Live, die and repeat

The game is still not over. What one must now do is bring the jigsaw pieces together by combining each party’s discovery in order to see the bigger picture of what really happened both on and off stage. This will necessitate a review of the incoming discovery to get the full facts in context. Often discovery will happen in stages ("rolling discovery") when the volume of documents is so large that it would be imprudent, or impossible, to wait until it is all ready.

Sink or Swim

While this entire process may seem quite straightforward, there are ample variables that make it hard to provide an accurate estimate up front, regardless of how experienced you are with discovery. As I mentioned earlier, it is not until the data processing stage is complete that we have any idea how many electronic documents there are and how much space they take up. These very elementary variables have a tremendous impact on cost, yet parties are still obliged to submit firm budgets quite some time before they have reached this level of awareness.

The global discovery industry has a number of ways of charging for what it does in support of the legal profession, and it seems no two discovery companies do it the same way (which, from experience, makes comparing budgets to identify the best deal a nightmare). Estimates are based on assumptions, and the ability to make good assumptions varies widely. One thing I can guarantee is that the only assumption that is always right is that nearly all assumptions will be wrong. Unfortunately, Precedent H doesn’t really allow for that.

Things that can Hole you Beneath the Water Line

(A1) Paper – scanning

In the world of document scanning there are a few very important elements that have an enormous impact on the cost.

Pages per document

The number of pages scanned and the number of documents coded will drive the final cost. At the point of estimating, one would make an assumption about the number of documents (based on the reported number of filing cabinets/drawers/boxes/bags/piles) and number of pages per document. That would lead to an estimate based on multiples of documents and pages. If the ratio proves to be wrong (and it usually is as there is no universal document size) then the final price will change (usually upwards). Unfortunately, it is impossible to know what the page count per document is until everything has been scanned.

Non-standard size

The cheapest way of scanning is to do it in bulk using automation: drop the pages in the automatic document handler and press "Go". This works well for pages of a "standard" and/or consistent size. However, bigger or smaller documents need to be handled manually. Manually equals more expensively.

Physical quality

Similarly, documents will only successfully journey through the scanner if they are sufficiently robust. "Old style" onion skin paper, fax sheets, carbon copy paper and the like (yes, they still exist) will almost certainly get chewed up in a modern automatic system, perhaps breaking machines in the process. These will therefore need to be handled manually. Manually equals more expensively.

Colour

Nowadays, with colour-detecting scanners, this is not such an issue but, when it is, automatic scanner settings will need to be altered on the fly to accommodate a change in the raw material. Colour pages may also need to be handled manually. Manually equals more expensively.

Binding

As mentioned earlier, in order to scan the documents/files they have first to be broken down into their individual parts. This means dismantling any binding and sticky-notes and separating all pages and then, once finished, reconstituting the binding and documents as faithfully as possible to the original (if required). I think you can now guess where this is heading: the less standard/more complicated the binding the greater the expense.

(A2) Paper – OCR

The success rate of optical character recognition varies dramatically according to a number of variables. These variables themselves have no impact on the cost of OCR (it is an entirely automatic process – as opposed to ICR (Intelligent Character Recognition, where manual intervention is required)). However, costs increase during the review phase as it is virtually impossible to filter the scanned images of the paper usefully if there is no, or limited, searchable text available. Furthermore, contextual searching ("find every form with a tick in the third box down on page two") is only possible with the right specialist software but is not available as a result of standard OCR processes.

Handwritten forms

OCR cannot read handwriting, so manuscript portions of forms will not be converted to text. Moreover, handwriting overlaying printed parts may compromise the electronic reading of those printed parts.

Complicated layout

Many OCR systems will not be able to cope with pages that contain complicated layouts, such as multiple columns or text that flows in "funky" directions.

Historical qualities

This may be obvious, but OCR also struggles with paper printed using older printers (like dot matrix printers or typewriters) where the individual letters are, on close inspection, actually made up of separate elements (so that to an OCR programme a "d" looks like a "c" next to an "l"). The same is true of old fax printers, as well as the hundredth photocopy of the hundredth photocopy of a much-loved form.

Annotations

Anything that causes the OCR to take its eye off the ball, such as circled, highlighted or underlined words, will confuse it. By example, a printed meeting agenda which has been annotated during the meeting is unlikely to be rendered well.

Physical defects

Paper documents lead tough lives. They tend to be old and to have been poorly treated over the years. It is not uncommon to see coffee rings, footprints, dirt, deep folds, tears and even tears. Each of these will compromise the quality of the OCR process.

Pictures

Nothing commonly available will render printed pictures searchable.

(B) Electronic

Compressed files

One would think that if you have collected data that eventually takes up X amount of space or contains Y amount of documents you would be safe to provide a cost estimate for subsequent activities relating to that data based on the figures that are X and/or Y. Yes? No!

It is common practice to shrink large but infrequently accessed data into smaller units so that they take up less space. This is the electronic equivalent of using vacuum compressed bags. Similarly, it is equally common to roll up multiple bits of data into a single unit which is smaller than the sum of its contents. I won’t go into the whys here, but in each instance you need to expand these back into useable units before you can do anything more with them. Thus, the X or Y you collected will be bigger than X and more than Y after processing because all the supposedly small things are now actual size. But you won’t know that until you have processed it all.

Encrypted files

Businesses encrypt data to keep it safe from prying eyes. They infrequently remember that fact as you collect that data, or sometimes they are unaware that some of their older data is encrypted. In either case, data processing is either diverted or halted whilst the key to decrypt them is found. The data will remain inaccessible if the key cannot be found.

Password-protected files

Password-protected files cannot be accessed without their passwords. Unlike encryption, however, password protection is usually an ad hoc process applied by the creator of that file. What this means is that the file is likely to contain data of importance to the creator but not necessarily of importance to the business. But without seeing it, who knows? If unavailable, passwords can still usually be cracked but it can be a time- and money-consuming exercise.

Embedded objects

These are "hidden" pieces of data that only reveal themselves during processing and so are not apparent when considering Y amount of items (but could be included in the X amount of space). They are not hidden as such, they are just referred to in a way that does not make them immediately apparent in a data "head count". Examples are a link to a spreadsheet from within a Word document or a picture inserted in (rather than attached to) an email.

Non-standard/bespoke software

There is often data that requires some other software in order to read it. One example is an Access database that is effectively unusable without also having the original database structure written specifically to interrogate and report on that isolated data population. It is impossible to make any sense of the data without that bespoke wrap-around. This is what people refer to as "structured data": you need the associated system to make sense of its structure and thereby gain access to the data. You cannot approach it meaningfully, much as you cannot open a lock without its key.

Most of us may be comfortable with "traditional" office software (word processing, spreadsheets, etc.) but occasionally a business will have something that is more rarefied, such as a computer-aided design (CAD) tool or a non-standard email system. If software like that is encountered and it is confirmed that it may be relevant, then traditional workflows and processes will need to be altered or new workflows created in order to accommodate their throughput. Basically, anything out of the norm usually costs more money to manage.

Incomplete data sources

Too often we come across incomplete sets of back-up tapes. It is nearly impossible to effect any form of data restoration without the complete set of tapes to hand. Many hours can be spent in discussion back and forth with a client’s IT team trying to find a good set of back-up tapes. One cannot sensibly allow a sum in the estimate for that.

Foreign language

Often, and especially in Europe, one can encounter unexpected tranches of content in a foreign language. Although this has no impact on processing it can have a significant time and cost impact on the review. Multi-lingual reviewers are required and it is necessary to adapt the review manuals to reflect the different language requirements and terms of art being sought.

(C) People

One should never overlook the extent to which humans can have an unexpected impact on the overall cost of discovery.

Custodians

As described earlier, custodians are those people who "own" potentially relevant documents. They may go on to become witnesses but the terms are not synonymous. Custodians's data will need to be collected once they have been interviewed.

The variables in play here are:-

- The number of custodians (this inevitably increases from the estimated number as the matter develops).

- Their locations.

- Their availability.

- Their helpfulness (c.f. good communications)

- The amount of documents they truly "own".

Assumptions about all of these are made at the time a cost estimate is prepared but they always change.

Names

This one is often overlooked: sometimes there is no individual who owns the documents, just an office, job role or function (such as "Cabinet Secretary" or "PMO"). That entity can be represented by any number of people over time and can often evolve into a multi-headed Hydra during the identification process.

Some executives are supported by a PA or EA who may correspond in their boss's names but, behind the electronic scenes, it is actually the PA's name over everything not their boss's (who is the custodian on the record).

It is also not unknown for custodians to change gender or otherwise change their names (through marriage, divorce or deed poll) during the relevant period.

Planning and preparation

Clients can directly influence the cost of some of the discovery activities. Generally, the more support they provide, the lower the overall cost. By example, great savings can be shown by having key people co-ordinated so they are available when needed, their computers available to have data collected, facilities available to use, senior managers aware of the processes and why they are necessary and all privacy and confidentiality issues dealt with up front.

However, beware: while a low cost option where the client intends to take a very active role may make economic sense, it can cause issues if the intent and respective roles are not clearly communicated to everyone involved. Also, it is generally wise to keep a potential witness away from these activities lest they cloud their knowledge or interpretation of past events

Last minute discoveries

This always happens! Whilst interviewing people and poking around in server and storage rooms someone inevitably remembers the storage facility down the road that contains heaps of on-point paper documents or the out-of-commission servers kept stacked in a cupboard that still have potentially relevant data on them. These all add to the final cost. As does a custodian innocently referring to their Gmail account or a thumb drive, each of which they have used for business purposes. Not to mention the home computer they share with their spouse, a doctor, and which both of them also use for business purposes.

Last but not least…

The opposition. Cooperation between the parties is required by the rules and is a Good Thing if both parties play nicely. However, no-one can ever allow for the time "invested" in dealing with an opponent who thinks that being cooperative is an excuse to waste time "trying" to agree key words, date ranges, collection methodologies, protocols and so on. Cooperation doesn't half cost a lot if not done properly!

Finally, I have yet to see one party provide the court with an estimate for the cost of analysing and reviewing the other party's discovery, but that is as necessary an activity as getting their own discovery out of the door.

Finally, wear a lifejacket

This article provides some indications as to why discovery estimates can change so rapidly through no-one's fault. There are no magic solutions to any of these issues. There are some actions an organisation can take to manage some of the costs:-

- Having sound information governance polices already in place is a most excellent start.

- When a dispute arises, retain an experienced discovery consultant who can advise regarding the issues and the best workflows and technologies to use based on the "Rumsfeld test" (known knowns, known unknowns and so on).

- Carefully review the consultant's pricing structure to determine whether it makes sense for the organisation and the dispute, that it is proportionate and there are no hidden charges hidden behind (for example) sliding scales of volume and time.

- Use a legal team with an understanding of the discovery process and insist on open communications among the various members of the team assembled to manage the discovery process. When required, allow the member with the most appropriate expertise to lead.

- Do not be resistant to change: expect to move with the ebb and flow of the shared journey.

Taking these steps can give you the lifejacket you need to prevent drowning when you are driven against the inevitable iceberg. Interested in knowing more? Contact the author, Jonathan Maas, or visit the Maas Consulting Group's web site.

Senior Business Development Manager at KLDiscovery (UK and Ireland) simon.manton@kldiscovery.com +44 (0) 20 7549 3856

3yWell worth a re-read..

Director, eDiscovery & Legal Disclosure Advisory | Incident Response | Cyber Risk Advisory EU & UK

5yThanks Jonathan, this only just caught my attention. I started back when paper was still the main corpus of a matter. Industrial scanners and manual bates stamping still happened. I love that there’s some strong guidance on dealing with paper as I feel many have forgotten the art. I still come across matters where paper discovery is essential so it’s good to see some sensible advice published on the topic!

Although written for a UK context, this article is a great summary of the e-discovery process, especially the challenges involved with collection, which are universal. I will share it with our GoldFynch clients. Well written!